Ever wonder why a betrayal is always equated with the expression, “You’re an evil, conniving snake,” or why someone greedy is likened to a crocodiled when someone says, “Buwaya kasi ‘yan,” and, most strikingly why – in spite of being adorable and innocent – puppies can still be demonized in the statement, “Tuta kasi ‘yan ng ibang bansa”?

Whether we are aware or not, our everyday use of these animalistic expression can affect the way we see animals in real life, and, more often, we unconsciously propagate the idea that animals are indeed bad as compared to humans.

But is this really so?

Once upon a time

A few hundred years ago, humans only had nature and a lot of killing time. Without the advanced technology available to us today, our not-so-great ancestors entertained themselves by observing the natural world. Thus, popular riddles, such as the ones below, entered our vocabulary.

Creative and engaging, these riddles made way for animals to be further characterized and used in our vernacular. Eventually, some sayings and proverbs that feature animals also surfaced:

- “Parang isdang kapak, Makintab sa labas, Ang loob ay burak (Like the mullet fish, Shiny on the outside, The inside is full of mud).”

- “Ang lahat ng gubat, Tirahan ng ahas (The whole of the jungle, Is a haven for snakes).”

The sayings are obviously two-pronged: They have surface meaning and intended meaning.

The first saying describes how the freshwater fish is shiny on the outside due to their scales, in contrast to the inside of their bellies which are muddy, because they ingest dirt from the water. But is this proverb really about fish? When spoken out loud, we notice that this is actually a sly comment directed at another person. Simply put, it implies that some people may look good and attractive physically, but can have really nasty and trashy personalities.

The second saying is brief but it quickly brings knife to the heart. Like in the first proverb, the quote is not at all directed at snakes. But the characteristics of both the jungle and the snakes are used to drive another point: that vile, poisonous creatures live in the unruly wilderness.

I can only imagine how the first person to say this thought of this expression. Was he thinking of a sloppy neighbor? A deceitful person who lives with other unlikeable people? Whereas a city is a civilized place for decent people, a jungle, in contrast, can be seen as the complete opposite – an uncivilized place, filled with animals who cannot be taught to act human.

“Othering”

From Plato to Darwin, people have always placed animals, quite literally, at the bottom of the food chain. In the heirarchy of beings, humans have always been just below the angels, or so we believe – and the animals, almost equal to plants and other inanimate, living, but non-breathing matter.

The knee-jerk instinct is to see how different they are from us. When we see a dog on the street trying to rid itself of ticks, we think of how we don’t just use one of our legs to scratch a spot on our neck, or how we don’t lick our skin when we want to remove dirt from our body. Birds can fly, but we don’t just go do number two right when we feel like it, and definitely not from the tree branches. Pigs like to muddle in the mud to stay cool, but we only see them as filthy creatures, unlike us who knows a couple more ways to stay cool without dirtying ourselves.

Are we really that different from them? Or do we just want to place ourselves higher in the great scheme of things, further and further from those creatures we simply call non-humans?

Of course, we don’t hate all animals. We even use some of them as metaphor for bravery (“like a lion in the face of adversity”), greatness (“an eagle soaring in the wind”), and luck (“that person escapes death like a cat”). But what happens when the people we loathe need some despising? We turn to the animal stereotypes to communicate our frustrations. And it is as if crocodiles are nothing but greedy reptilian counterparts of humans, snakes are tricksters who bite when given the chance, and dogs are just barking metaphors for blind loyalty.

When we notice bad habits, harmful decisions, and offensive statement from our own kind, the most convenient move for us is to project these things to other species. What we deem as unacceptable behavior to us, we assign to animals whom we think best mirror these, ignoring their other amazing and unique qualities as individuals.

The harm that builds a barn

At this point, you might be saying, “So, what?”

Who care if we use not-so-animal-friendly phrases a few times a week? Where is the harm in that? We don’t actually bully puppies in real life whenever we equate blind followers to them. In fact, what we see as a likeable quality in puppies only turnes sour when applies to a human being. What’s the worry?

As tools in society, language and rhetoric not only reflect our worldview, but also shape it. It is a vicious cycle if we use language that is divisive, discriminatroy, and demeaning. When we say, “Our Congress is teeming with crocodiles in barong tagalogs,” we are not only providing critique of the legislature, but also reinforcing the idea that crocodiles are greedy creatures. And this idea isn’t at all true!

Busting the myth

For our 411, crocodiles only eat once to thrice a week, and consume only what their body needs. Unlike human beings who consciously take more than what they need or what isn’t rightfully theirs (big oof), animals, such as crocs, do not succumb to this ironically very human tendency.

In a very similar way, equating a person who is lacking in either intelligence or courage to a chicken (“He’s got chicken brain!” and “Can’t do it? What a chicken!”) paints actual chickens as brainless and cowardly, which further perpetuates cruelty and violence against them.

Likewise, when we see pigs as squalid beasts who eat garbage rather than intelligent creatures (even smarter than dogs) who can think, feel, and remember, it makes it easier for many of us to treat them badly. Whom we don’t see as individuals like us, we can, without hesitation, see as inferior – beings who do not deserve the same consideration and respect we give to our own species.

Tweak the speak

Okay, so maybe none of us really want to harm animals – at least, not in the way we express ourselves. We can still voice out our frustrations, be funky i our rhetoric, say more than what we mean, and speak in code.

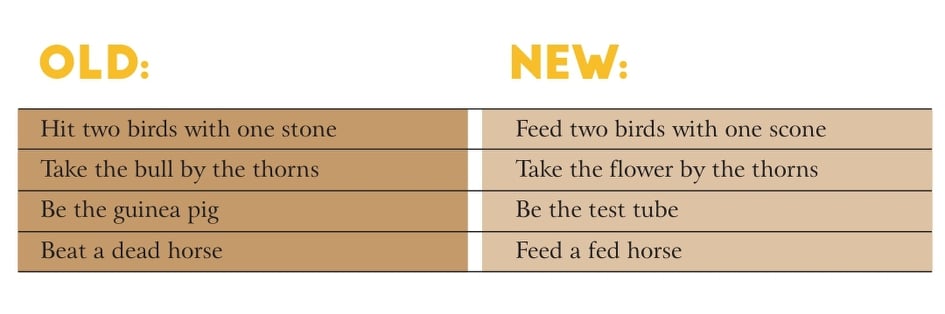

Recently, the organization People for Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA) released an article that encourages the use of more animal-friendly versions of old common idioms. Here are a few of them.

This attempt may be small, but it just goes to show that words and phrases can be arbitrary, and that they should be changed if necessary. There are a lot of different ways to express the same sentiments, and we can choose to say the ones that don’t perpetuate harming others.

Here’s a difficult truth: It takes a long time for us to achieve the change we want. It takes years, maybe even a lifetime. Perhaps we can, little by little, change the way we converse about animals or how we refer to them in our language. Maybe this is a small feat for us, but it affects them in more ways that we can think of, and most of the time, the effect is harmful.

Our distaste for our own kind’s follies have nothing to do with animals or their unique qualities and characteristics. For now, maybe it’s time we leave them out of this kind of talk.

This appeared in Animal Scene magazine’s November-December 2020 issue.

You might want to read:

– Do all dogs go to heaven? Study shows fur-parents certainly think so

– Tired to talk to fellow humans? These pet owners are teaching their companions to speak instead

– Cats are talking to you with their faces, study explains