By ALEX BICHARA

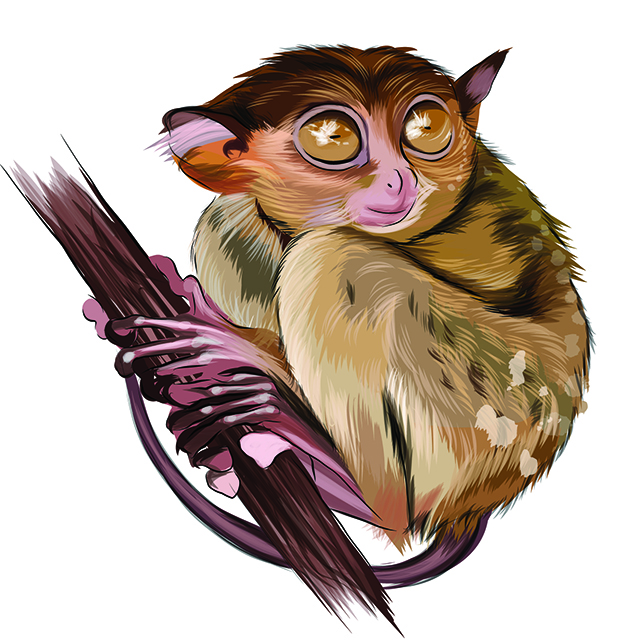

When Typhoon Odette made landfall in the Philippines in December 2021, it claimed over 400 human lives, according to a 2022 Rappler article by Jairo Bolledo. Its effect on the country’s nonhuman animal population wasn’t immediately seen, except in the disappearance of over a hundred Tarsiers from the Bohol Tarsier Conservation Area.

According to the Manila Bulletin, only two out of 150 tarsiers being kept at

the sanctuary were sighted immediately after the storm. When photos of a lone tarsier holding on to a tree trunk amid ruins went viral after being posted on the Facebook page of CinemaBravo, netizens were quick to ask what went wrong.

THE BOHOL TARSIER CONSERVATION AREA

The Bohol Tarsier Conservation Area is a forested sanctuary in Loboc, Bohol that’s often part of packaged tours including the Chocolate Hills, which can be found nearby. According to blogger Mike Raquel, the Tarsier Conservation Area was founded in 2011 and provides tarsiers with six hectares of natural habitat.

Tourists are able to roam the sanctuary while following several rules to respect the Tarsiers. Aside from not being allowed to touch the Tarsiers, tourists are also advised not to use flash photography inside the sanctuary. Considering that Tarsiers are nocturnal animals, guests are also asked to observe silence when they visit.

AFTER THE STORM

After the events of Typhoon Odette, the Philippine Star reported that only two Tarsiers could be seen in the conservation area’s viewing section (Severo, 2021).

In an interview with “Unang Balita”, a GMA News segment, Bohol Tarsier Conservation Area Manager Jennie-Lee Dical explained that the Tarsiers were no strangers to typhoons. In fear of storms, the Tarsiers tend to seek refuge under rocks or “big branches” of trees.

This is of note because Tarsiers are often described as exhibiting suicidal behavior after just hearing loud noises, as reported by Jan Milo Severo in a 2021 article for PhilStar.

SENSITIVE, ANXIOUS CREATURES

The Philippine Tarsier is a species that’s around 45 million years old. According to CNN, they’re also the second-smallest primate on earth at just about six inches long and three to five ounces in weight, as reported by Kate Springer in a 2017 article for CNN. Because of its tiny size and large eyes, many associate the species with Yoda, the legendary Jedi Master from Star Wars.

Unlike their hundreds-years-old fictional lookalike, however, Philippine tarsiers have a lifespan in captivity of around twelve years. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species currently lists the species as “near threatened” with a decreasing population due to residential and commercial development, agriculture and aquaculture, and biological resource use or hunting and trapping.

What many find odd about Tarsiers is its tendency to turn suicidal. Tarsiers are more sensitive and anxious than most other animals, heavily affected by factors such as physical contact, daylight, and noise. Confined to cages, Tarsiers have been known to hit their heads against the cage walls, cracking their skulls in the process, reported Joanna Zelman in a 2011 article for Huffington Post.

Though they are a major tourist attraction in Bohol, Tarsiers are also constantly threatened by national disasters similar to Typhoon Odette.

A 2017 study on the impact of Typhoon Haiyan in 2013 on the Philippine Tarsier population found that the typhoon “significantly affected the density of the Philippine Tarsier” in the Philippine Tarsier and Wildlife Sanctuary. From a Tarsier density of 157 individuals per square kilometer, it became 36 individuals, illustrating the devastating effect of a single typhoon on the Tarsier population, according to Sharon Gursky and colleagues in a 2017 study published in Folia Primatologica.

Perhaps it is time to put a spotlight on the nonhuman animals especially threatened by the natural disasters the Philippines is so prone to, so that we may never suddenly lose a hundred of our most vulnerable creatures again.

HOW HUMANS PLAY A ROLE IN TYPHOON STRENGTH

There are many theories surrounding the link between human activity

and typhoons, though factors such as limited satellite observation make proving these theories a challenge.

According to Emily Becker, the Associate Director at the University of Miami Cooperative Institute for Marine and Atmospheric Studies, one theory involves the warming of oceans due to the heat-trapping effect of greenhouse gases. The warm air from the ocean surface then rises, leading to the creation of thunderstorms.