“Yuck!” This is the word I hear most often uttered by people who chance upon the Cane Toad. Such a reaction is quite understandable; this Amphibian is hardly the most comely of animals with their warty skin, yellow-brown splotchy complexion, and bulging eyes.

Add to that the fact that they’re widely known to be poisonous, and it’s of little wonder many humans cringe at the sight of one.

Rhinella marina, formerly known as Bufo marinus, is sometimes called the Philippine Bullfrog. But a careful observer would immediately note their relatively short legs and bumpy texture and realize that this creature is definitely a Toad and not a Frog.

Like most of their kind, the Cane Toad tends to crawl rather than hop. Though when they do choose to hop, they can do so with startling speed.

Adult Cane Toads commonly grow to lengths of over 6 inches and can weigh almost 3 pounds, making them the largest Toads in the world. Giant specimens have been known to reach lengths of 9 inches. An amphibian of that size bounding across one’s lawn can, understandably, be quite discomfiting to some people. And the first instinct is usually to either avoid them or get rid of them.

Good luck getting rid of them, though. Scientists and agricultural experts have been trying to figure out ways to control Cane Toad populations for decades.

A GUEST WHO STAYED

Cane Toads are considered an invasive species in the Philippines, but what that simply means is that they are not native to the country and can cause harm to the ecosystem. They did not settle in the Philippines by choice but were brought over by agriculturists in the 1930s from their original home in South and Central America.

Those who’d introduced the Toad to our shores hoped that the amphibian, known for their hearty appetite, would help control insects and other creatures capable of damaging crops. As expected, the voracious Toad ate them; however, they also devoured everything else, including beneficial insects.

In addition, the Toads also ate fledgling birds, reptiles, other amphibians, and even small mammals. This ability to eat almost any other animal they could catch and stuff into their mouth was one of the things that enabled Cane Toads to reproduce and propagate themselves to the point that they could soon be found in almost every corner of the country.

And the damage they inflicted outweighed the benefits they brought. A study by the International Rice Research Institute showed that less than 10 percent of the insects consumed by the non-native Cane Toads were those identified as crop-damaging (as opposed to over 50 percent, in the case of certain indigenous Amphibians such as the native Luzon Wart Frog.)

The Philippine experience is hardly unique as many other countries brought Cane Toads into their territories with similar hopes that they would control agricultural pests. An article published in National Geographic narrates how “In 1935, at the request of sugarcane plantation owners, the Australian government released about 2,400 Cane Toads into north Queensland to help control cane beetles, which eat the roots of sugarcane.” With no natural predators and an ability to reproduce rapidly, they spread quickly and widely and soon numbered in the millions and established populations in thousands of square miles in northeastern Australia.

The Cane Toad was also introduced into North America and has become a problem in states like Florida and Hawaii, as well as in the islands of Guam and New Guinea.

POISONOUS FROM BIRTH

Even in their countries of origin, Cane Toads have few predators. One reason is that they are highly poisonous throughout every stage of their life cycle. Eggs, tadpoles, and adults all contain or produce a form of toxin that can cause hallucinations and heart problems, possibly resulting in death for animals that attempt to eat them.

Only a small number of predatory reptiles and fish are immune to Cane Toad poison and are thus capable of eating them.

Adult Toads secrete a substance containing steroidal toxins called bufagenins, in the form of a milky white fluid from parotoid glands found on the back of their necks and shoulders, and it is this substance that is believed to be responsible for a number of fatalities involving small Dogs that bite them or pick them up with their mouths. Even if the Dog immediately releases the Toad, the poison is quickly absorbed by their gums and other mouth membranes and can cause tremors, seizures, and cardiac arrest.

Humans are similarly affected if they consume the poison, and there are accounts of people dying after having cooked and eaten a Cane Toad.

EFFICIENT REPRODUCERS

As if having very few natural predators wasn’t enough, Cane Toads are highly efficient at propagating their species.

They breed all throughout the year and need only a small body of freshwater in which to lay their long strings of eggs that can number up 30,000 (most species of Frogs and Toads produce less than 2,000 eggs, which is why Cane Toads often quickly out-compete native amphibian species wherever they settle.) From these hatch tadpoles that develop into full-grown Toads in as early as two weeks.

The Toads start reproducing when they reach two years and can live for up to ten years in the wild, though five is more common. In captivity, Cane Toads have reached ages of up to fifteen years.

A SCIENCE LAB MAINSTAY

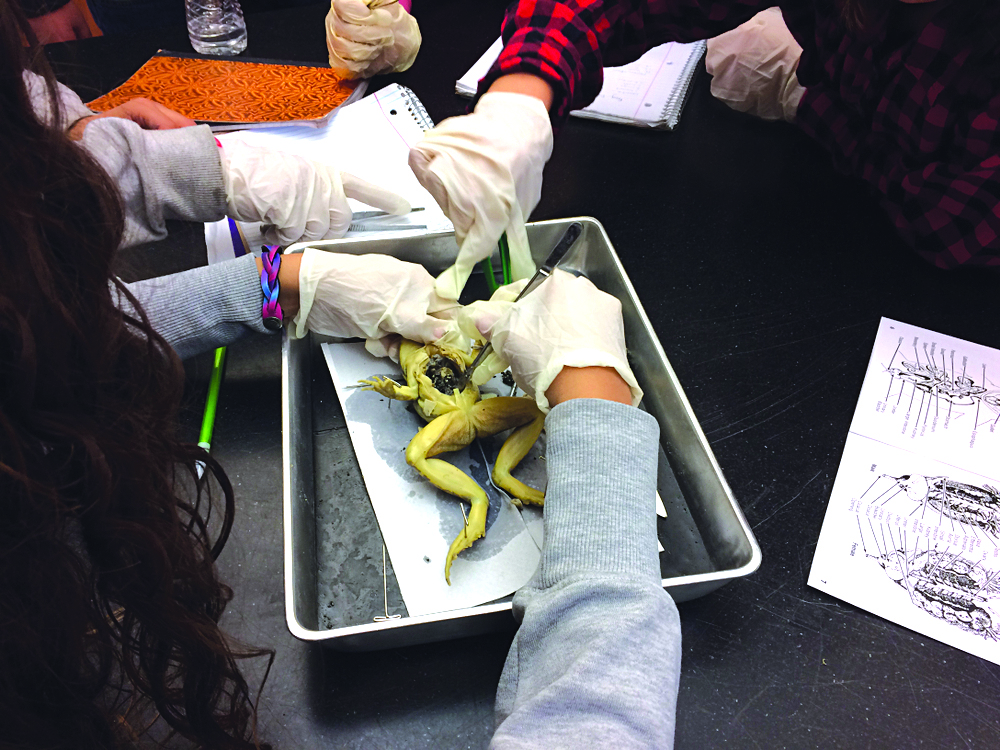

Perhaps the only place where Cane Toads have become and remain popular is inside science laboratories.

In the Philippines, there is no animal more frequently sacrificed at the altar of science education than Rhinella marina. Every year, thousands of Toads are anesthetized and cut open in biology labs and classrooms in an attempt to understand vertebrate anatomy.

Since Cane Toads are an invasive species, their harvesting is not regulated by any laws and such experiments are actually viewed by some as a means to control the population. [Why is it that animals often pay the price for human shortcomings? -Ed.]

The poison that Cane Toads produce has also been the subject of study, especially after it was found to be more complex than previously thought. Scientists have analyzed the toxins in efforts to “better understand the enemy” as well as to explore the possibilities of using them in medical procedures.

QUO VADIS, MR. TOAD?

The Cane Toad is destined to remain a cautionary tale for anyone thinking about bringing in exotic species into a foreign territory without adequate study. But while we sometimes cannot help but decry the negative ecological impact Cane Toads have had upon the habitats into which they were introduced, we also cannot help but admire this remarkable animal’s resourcefulness and resilience.

Cast into a foreign and unfamiliar environment, these amphibians wasted no time adapting to their new surroundings, finding ways not only to survive but to actually thrive.

Their displacement of some native species and the subsequent disruption of certain processes is, one might argue, part of the circle of life wherein only the fittest survive. And in this often unforgiving cycle, the Cane Toad has proven themself among the fittest of the fit.