The fictional Moby-Dick was based on a real albino bull sperm whale called Mocha-Dick, whplied the waters off Chile in the early 19th century. Nearly indestructible but defending himself when provoked, Mocha-Dick was said to have survived over a hundred battles with whalers, destroying 20 boats in 30 years.

He was tragically killed in 1838 and only because he tried to help a mother sperm whale and her calf who were being slaughtered by whalers. Measuring 70 feet, his body yielded 100 barrels of oil and, more impressively, 19 embedded harpoons from earlier battles.

The true tale of the whaling ship Essex, destroyed by another albino sperm whale in 1820, was retold in the 2015 movie In the Heart of the Sea. I read a bit more about whales because of the movie and a book project on the Essex.

Recounting the tale last month, my audience responded with disbelief. “Whales? In the Philippines?”

Not many Pinoys know our country has whales. Forming the apex of the Coral Triangle, the Philippines has 3,000 recorded species of fish, plus 30 types of cetaceans.

Cetaceans (pronounced se-tay-shuns) include about 90 species of whales, dolphins and porpoises which range across the world’s oceans. They’re mammals, not fish. Philippine cetaceans range from the 2.5 meter Irrawaddy dolphin to the 30 meter blue whale.

“Cetaceans are extremely important for the marine ecosystem,” says Marine Wildlife Watch of the Philippines Director Dr. AA Yaptinchay. “Most are apex or top-level predators which regulate populations of fish and squid, thereby keeping the ecosystem balanced to promote diversity. The bigger whales, especially filter-feeders, contribute to nutrient distribution in the sea through a ‘whale pump’, thereby fertilizing the sea surface with their poop, which encourages plankton growth.”

I recently got the chance to look for wild sperm whales for a TV show in Bais City, 45 kilometers north of Dumaguete in the Tañon Strait. The Tañon Strait separates the islands of Cebu and Negros and is home to 14 species of dolphins and whales. Droves of tourists visit the area to see these magnificent mammals up close.

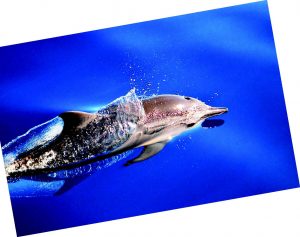

Each species has its own personality: bottlenose dolphins stay near the shallows, while acrobatic spinner dolphins leap and twirl in open water. Larger Risso’s dolphins like to float upside down, tails sticking out of the blue.

BYCATCH

Once widely hunted and slaughtered for meat and blubber, all cetaceans are now protected in the Philippines by the amended Fisheries Code. Still, many die because of accidental entanglement in fishing gear, which can cause the air-breathing mammals to suffocate or drown.

Known as ‘bycatch’, this causes the deaths of over 300,000 whales, dolphins, and porpoises globally every year. Other threats include marine debris and plastic pollution, habitat destruction, overfishing, and hunting, which sadly still occurs in remote parts of the country.

“Charismatic creatures like dolphins bring in millions of pesos from ecotourism, enriching the lives of locals. We work to conserve fisheries by looking at the no-nonsense implementation of our fisheries and environmental laws to protect marine ecosystems and resources. This ensures that our beloved dolphins will always have food to eat, while protecting the livelihoods of our coastal residents. When done right, tourism is solid proof that many animals are worth more alive than dead,” says Atty. Gloria Estenzo-Ramos, head of environmental group Oceana in the Philippines.

We sailed around the Tañon Strait for hours, encountering hundreds of spinner dolphins, several bottlenose dolphins and even a pair of rare pygmy sperm whales from afar! Growing just over three meters, they’re just a bit larger than dolphins but much more elusive. We only saw them for a few minutes before they disappeared into the deep.

Though we didn’t see giants like Mocha-Dick in Bais, we know they’re still there. In 2016, a blue whale, the largest animal on Earth, was spotted off the coast of Dumaguete, proving that despite centuries of whaling, the planet’s largest and most majestic animals are still hanging tough.

I just hope that better conservation and management will birth a new generation of giants, inspiring Pinoys to protect not just cetaceans, but all our home waters.

This appeared in Animal Scene magazine’s April 2018 issue.