What looks like a carabao but moves like a deer? What is revered by Mindoro’s Mangyan people and harried commuters alike? None other than the tamaraw – and this month, Animal Scene celebrates Tamaraw Month by taking a closer look at the country’s most iconic mammal.

Just half a century ago, these ferocious dwarf buffalo teetered on the edge of extinction. Read on to realize the value of conservation.

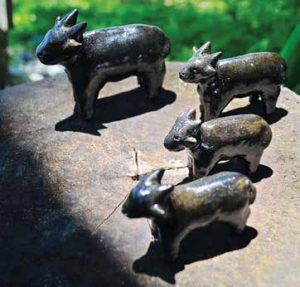

Petite and Popular

The Suncor Nodosaur is now known to science as Borealopelta markmitchelli – roughly translated as ‘Mark Mitchell’s northern shield’ after the technician who freed it from rock. It is now the most perfectly-preserved dinosaur ever found.

Mindoro’s Forest Buffalo

According to a 2013 article by the Mohamed bin Zayed Species Conservation Fund, “It is the only wild cattle species living in the Philippine archipelago.”

Adult tamaraw are about four feet tall and can weigh over 300 kilograms. Their coats range from reddish brown to a glossy black.

About a thousand years ago, tamaraw inhabited all of Mindoro – from low-lying meadows to mist-shrouded mountain peaks. In the 1900s, the population was estimated at over 10,000 heads.

Despite being just 160 kilometers from Manila, Mindoro was relatively uninhabited until a century ago. It was the humble mosquito that prevented the colonization of the island, as malaria proved deadly to outsiders.

At the time, the island was chiefly inhabited by small, roving tribes – the Alangan, Bangon, Buhid, Hanunuo, Iraya, Ratagnon, Tadyawan, and the largest, the Taw’buid (whom I had the honor of visiting last year for a Nat Geo story).

Carabao or Tamaraw?

Though it may look like a carabao, the tamaraw is an entirely different species. Whereas carabaos are larger and are armed with long, C-shaped horns, tamaraw have short, V-shaped horns. Tamaraw move quite differently, being more agile, skittish – and prone to charge when provoked!

Disappearing Act

After establishing footholds in centers like Puerto Galera, settlers started converting more and more of the land for agriculture, forcing both the tribes – which outsiders collectively called Mangyan even today – and the island’s wildlife to retreat higher and deeper into the mountains.

In the 1930s, a stunning blow came by way of rinderpest – a deadly, cattle-killing disease which nearly wiped out all tamaraw, plus loads of deer and introduced cattle. By 1969, scientists estimated the global population to be under 100 animals – prompting the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) to classify them as critically endangered, the highest risk rating for any species.

The government, local communities, plus conservation groups like the World Wide Fund for Nature and Mindoro Biodiversity Conservation Foundation Incorporated then stepped in to save this proud forest buffalo from the brink.

More Tamaraws Tomorrow

Animal Scene readers who are bush-savvy and wish to see the tamaraw in their natural element can trek up the Iglit-Baco mountain range in Occidental Mindoro – a two-day hike full of mud and leeches.

One thing’s for sure: With continued protection, these iconic dwarf buffalo will continue to hold out in the grassy slopes and forest patches of Mts. Iglit, Baco, Aruyan, Bongabong, Calavite, and Halcon. So please help the country celebrate Tamaraw Month by sharing what you just learned online with the hashtag #TamarawMonth!

Many Years of Conservation Later

The Philippine government is ably leading tamaraw conservation efforts. It is enforcing four national laws against tamaraw poaching: Commonwealth Act 73 plus Republic Acts 1086, 7586, and 9147. Under RA 9147 or the Wildlife Act, hunters can incur from six to 12 years of imprisonment plus a fine ranging from R100,000 to 1M for harming and killing tamaraw.

Since 1979, the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) has been working tirelessly through the Tamaraw Conservation Program to boost buffalo numbers.

Through the support of allies like FEU, WWF, MBCFI, the local government of Occidental Mindoro, and indigenous Taw’buid tribesfolk, a consortium called “Tams-2” aims to double the number of wild tamaraw from 300 at the project’s inception to 600 by 2020, according to an article by Yasmin Caparas published in the DENR website.

Conservation efforts are paying off handsomely. From a 1991 survey which found 133 heads, numbers have jumped up to 523, as counted by the government and conservation organizations last April and reported by Madonna Virola of the Philippine Daily Inquirer.

“The total count of tamaraw increased this year because of various factors. However, it is a major concern that their home range is shrinking, causing their population to be concentrated in a small area. This results in overcrowding and increased competition for limited resources,” says Mindoro Biodiversity Conservation Foundation Incorporated Research Programme Manager Don Geoff Tabaranza.

Adds Fausto Novelozo, chief of all Taw’buid tribesfolk, “Kung walang tamaraw, wala rin po kami. Ang kabuhayan nami’y nakasaad sa yamang buhay. (Without the tamaraw, there will be no Taw’buid. Our lives and livelihoods are inextricably tied with biodiversity.”)

This appeared in Animal Scene magazine’s October 2018 issue.