Magnificently marked with stripes that help them blend perfectly in the savannas, forests and scrublands where they stalk, tigers (Panthera tigris) are in my opinion the true king of beasts — more capable, regal, and majestic than even Africa’s lions. And these big cats are rising from near-extinction.

A century ago, nine types of tigers roamed Asia and parts of Europe. Amur, Bali, Bengal, Caspian, Indochinese, Javan, Malayan, South China and Sumatran tigers preyed on deer, pigs, cattle and other animals whose natural populations were still stable. According to National Geographic, during the turn of the century, 100,000 wild tigers still lived — each eating up to 50 deer-sized animals yearly! A University of the Philippines study even revealed that tigers once thrived in the jungles of Palawan!

Unlike pack-hunting lions, tigers hunt alone and use their stripes to blend into the dappled world of the forest, stealthily creeping up to their targets from behind and dispatching them with a quick and efficient bite to the neck.

Humans versus Tigers

Tigers’ hunting territories are vast — spanning thousands of kilometers per animal — and are usually determined by the amount of prey. The shrinkage of this territory remains one of the most serious challenges for tiger conservationists. Over 93 percent of the tiger’s original territory has been cut down for agriculture and timber production, forcing these hunters to prey on livestock and occasionally, people.

Should we have captive tigers in zoos?

A contentious issue is the keeping of captive tigers, at least 20,000 of which live in zoos and private collections worldwide. About 5,000 are kept in North America and another 5,000 in China, where the big cats are controversially bred to supply parts for the traditional Chinese medicine trade.

Champawat and the Challenge of Human-Wildlife Conflict

Tigers are among Earth’s most efficient hunters, able to bring down everything from crocodiles to Asian elephants. From an ecological standpoint, they regulate herbivore populations, allowing grasslands and forests to grow optimally. As tiger habitats were cleared from the 1800s onwards, however, their prey disappeared, forcing many animals to resort to desperate measures to survive. Since then, some tigers began to hunt humans, terrifying thousands of people, particularly in population-dense India where the largest number of wild tigers thrive.

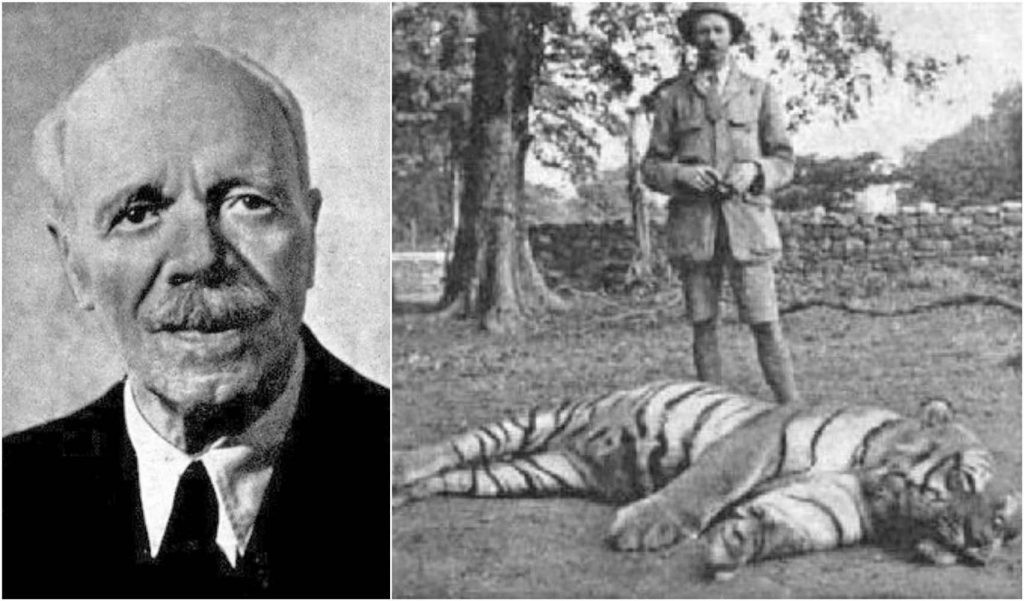

Feared above all was the legendary giant tigress, Champawat. From 1903 to 1907, she killed 436 people in India and Nepal before eventually being put down by conservationist Jim Corbett, who theorized that “circumstances beyond her control forced Champawat to adopt a completely alien diet.” Corbett was right, as the tiger was found to have broken teeth caused by an earlier gunshot wound – leaving her unable to hunt her usual prey.

In fear and reprisal for human and livestock attacks, people killed tigers by the thousands, with a tigress being clubbed and run over with a tractor in India as recently as November 2018. Because of this, four of the nine tiger subspecies — Bali, Caspian, Javan and Sumatran tigers — are now extinct.

To reduce human-wildlife conflict, tiger territories must be closed off to humans and a system for transferring overly-aggressive animals to more remote locations must be enforced. Still, wildlife conservationists acknowledge the difficulties of managing one of the world’s most efficient predators, especially in highly-populated rural areas. It’s an equation no one has been able to solve yet.

Big cat, big conservation effort

Tiger conservation began in the 1970s, with the establishment of the World Wildlife Fund (WWF), which chose the charismatic creature as a flagship species and began efforts to consolidate tiger protection efforts. Still, tiger numbers steadily plummeted from continued habitat loss and hunting for the deplorable trade in tiger parts.

By 2010, wild tiger numbers were estimated at just 3200, a 97 percent decline from the 1900s. I was a young officer working for WWF when top brass decided it was time for drastic action.

Since renamed the World Wide Fund for Nature, WWF came up with an ambitious programme called Tx2 or “Tigers Times Two” — to double the number of wild tigers from 3000 to 6000 by the next year of the Tiger in 2022.

WWF convened the governments of the 13 remaining countries where wild tigers still lived: Bangladesh, Bhutan, Cambodia, China, India, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, Nepal, Russia, Thailand and Vietnam. At the historic Saint Petersburg Tiger Summit, a global tiger recovery plan was crafted. This was a concrete plan for each country to meet its specific Tx2 targets.

After eight years of hard, uphill conservation work, the world’s tiger population is slowly recovering — the first time in a century. From 3200, numbers are rising, with 3900 today and more born yearly. Nepal alone doubled its wild tigers in less than a decade — the first tiger range country to do so.

“This is a pivotal step in the recovery of one of the world’s most endangered and iconic species,” said WWF’s Ginette Hemley for a Time Magazine interview. “But much more work and investment is needed if we are to reach our goal of doubling wild tiger numbers by 2022.”

Machali, champion of tiger tourism

Compared to a pelt and some bones, what is the value of a live tiger? From Champawat, let’s look at another legend: Machali, Queen Tigress of Ranthambore.

Inhabiting the Ranthambore National Park in India, Machali was the most photographed tiger on Earth, helping the Indian government earn almost USD 100 million from 1998 to 2009, according to a statement released by the park.

That’s PHP 5.3 billion in revenues. For one live tiger. Before she died of natural causes at the ripe old age of 20, she had her own commemorative Indian stamp, numerous documentaries, a lifetime achievement award, and a Facebook page followed by over 100,000 fans. More importantly, Machali gave birth to 11 cubs over the years. Today, half the tigers in the park come from her lineage.

The roaring, colorful story of tiger conservation goes on — and though we have made good progress, we must sustain momentum and ensure that we really hit 6,000 wild tigers by 2022. And I hope more of them turn out to be Machalis rather than Champawats.

This appeared in Animal Scene magazine’s April 2019 issue.