Spoiler alert! It’s because we ate them

It isn’t uncommon for animals to go extinct. Extinctions especially make the news every time the International Union for Conservation of Nature changes a species’ status on its Red List, telling the world which animal, fungi, or plant species is in danger or is in the clear.

But while studies like paleontologist David Jablonski’s 1986 academic article on mass extinctions suggest extinctions are natural to the process of evolution, there is also evidence that humans have played a significant role in the permanent loss of several animals.

In fact, according to a 2019 National Geographic article on extinction written by Liz Langley, humans have accelerated “natural extinction rates due to our role in habitat loss, climate change, invasive species, disease, overfishing, and hunting.”

Many of the aforementioned causes can be directly linked to which animals humans have chosen to put on their plates throughout history.

ANIMALS WE ATE OFF THE EARTH

The following are just a few of the animals we’ve lost to extinction due to human appetite, cementing our need to look beyond what’s for lunch and examine the effects of our individual choices on our planet.

PASSENGER PIGEON Ectopistes migratorius

The Passenger Pigeon is believed to have once been the most common Bird in North America.

According to the National Audubon Society, Potawatomi tribal leader Simon Pokagon recalled hearing what sounded like “an army of [H]orses laden with sleigh bells” and “distant thunder” coming closer and closer to where he was camping in May 1850. The sounds turned out to be millions of Passenger Pigeons, and this type of sighting was common around that time. These Birds were so abundant, they would darken the skies for hours as their flocks would migrate.

Today, they are but a memory immortalized in history books. While there might have been billions of Passenger Pigeons in existence in their heyday, humans would kill millions of them a year until the only live Passenger Pigeon left was a captive one named Martha.

Martha, who never laid a fertile egg, lived to the age of 29 and passed away at the Cincinnati Zoological Garden on September 1, 1914.

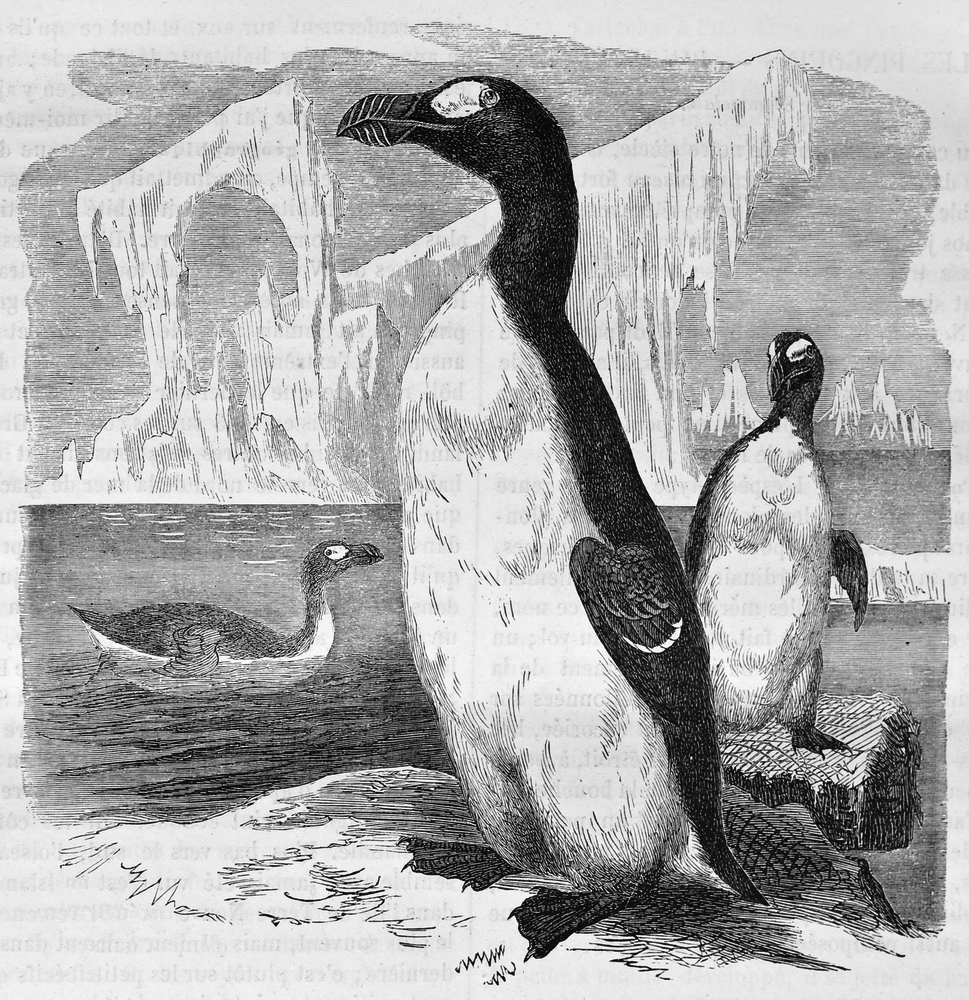

GREAT AUKS Pinguinus impennis

Similar to the Passenger Pigeon, the Great Auk was once upon a time a very common Bird. Though these Birds looked similar to the Penguins we’re all familiar with today, the Great Auk was native to the North Atlantic. They were, however, also flightless, making them easy targets for fishermen and hunters.

According to a National Geographic entry on the species, the last Great Auks are believed to have been killed by fishermen on July 3, 1844, in Iceland. By then, the species that used to be sold as food, bait, and other commercial goods had already been recognized as overhunted. Museums began collecting their skin to keep them on display.

While no one’s certain why the fishermen killed the last Great Auks in 1844, there’s no denying the effect human appetite had on the Great Auk species.

EURASIAN AUROCHS Bos primigenius primigenius

Eurasian Aurochs are considered the wild ancestors of today’s domesticated Cattle.

While they were huge (with an average height of six feet) and known to be aggressive, Aurochs were hunted for food and for game. Their temperament also led to their being used in battle arenas in ancient Rome.

An article on the Aurochs, written by Daniel Foidl on the Extinctions website, cites the Aurochs’ vanishing as having been caused by anthropogenic factors: They were eaten and hunted, infected by disease-riddled domestic Cattle, then driven away from their natural pastures for livestock.

Foidl writes, “It is the largest terrestrial mammal that has been exterminated by man in historic times.”

WATCHING WHAT WE EAT

Despite these incidents of extinction, there is still hope for the animals we’ve become so familiar with today.

The 2018 Living Planet Report by the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) stated, “We are the first generation that has a clear picture of the value of nature and the enormous impact we have on it. We may also be the last that can act to reverse this trend.”

Animals Australia, an animal protection organization, has also echoed WWF’s call to action, emphasizing, “The systems of ‘food production’ we inherited from those before us are having catastrophic impacts on animal species worldwide. And although we didn’t choose these food systems, we can change them.”

While we may have little control over the vast livestock agriculture industry in our

daily lives, there is much to be said about how our individual choices contribute to the continuous culinary demand for these sentient beings—especially when we already know how easy it is to lose them.