With recent news that two Southern Californian Condors apparently had no males involved in how they gestated from cells to animals, giving birth without the need for sexual reproduction has become a somewhat hot-button topic.

PARTHENO-WHAT?

Parthenogenesis is literally the term used when a female gives birth to offspring without any sexual reproduction involved – in effect, it is the physical capability of having a “virgin birth.”

THE DETAILS OF THE ABSENCE MALE BIRDS IN THE PROCESS

What makes the case of the fatherless Condors so interesting are the following.

UNKNOWN HISTORY

No one knows if Condors have always had parthenogenetic characteristics. With California Condors still endangered and scientists having an understandably small genetic database for the species, there’s not enough information to find out about Condors and their probable ability to be parthenogenetic.

POSSIBLY NOT PARTHENOGENESIS

When the female Condors became pregnant parthenogenetically, they were

with fertile males – so there must be some other mechanism for them to become parthenogenetic, not because there weren’t enough males left, as explained by Rebecca Coffey in a 2021 article for the Forbes website.

With this in mind, it’s unusual that there are Condors who can have virgin births at all. But does that mean to say that this doesn’t happen much in the animal kingdom?

SOMETIMES A QUIRK, MANY TIMES A SURVIVAL TRAIT?

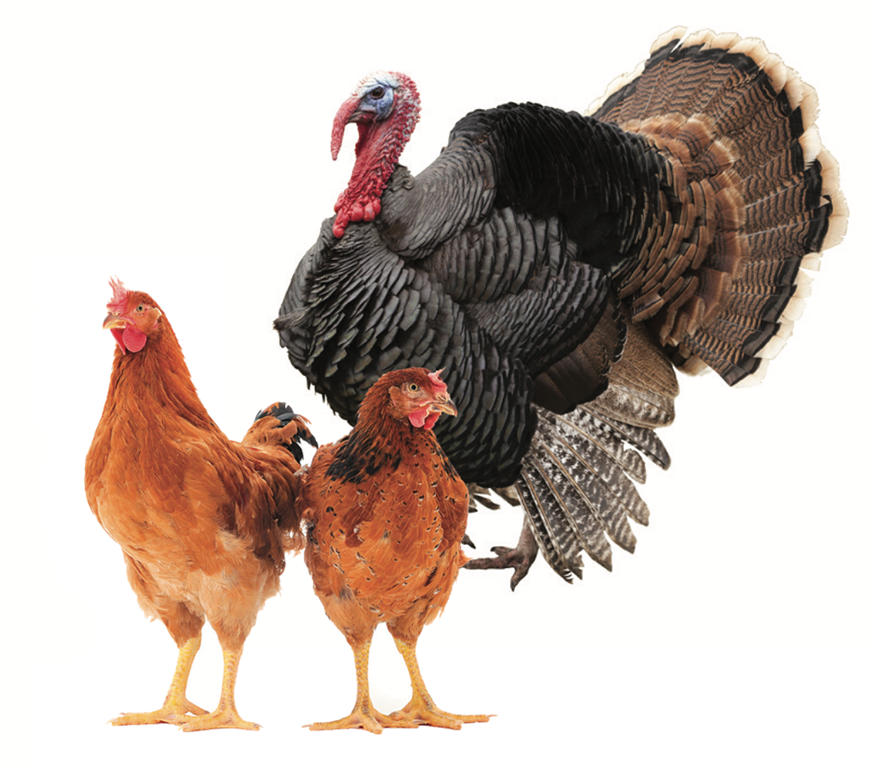

Parthenogenesis in the animal kingdom apparently isn’t a common thing, but it does happen. Birds such as Turkeys and Chickens apparently can do it. Some species of Fish, Reptiles, and Scorpions are also parthenogenetic as well.

While there are obvious advantages to the capability of females to have virgin births (particularly when it comes to population numbers), some scientists believe that parthenogenesis is not as good as sexual reproduction, in the sense that evolution by the mixing of genetic traits does not happen.

VIRGIN BIRTH AMONG HUMANS: IS IT POSSIBLE?

The possibility of a human female giving birth to an infant without any need for sexual relations with a man is technically possible, with the use of biochemical methods. The serious ethical issues, however, should be sorted out.

And – this is where we go into the domain of body horror – the truth is, some women have already had parthenogenesis happen, though in an imperfect form.

When parthenogenesis happens in women, an egg in the ovary begins to develop on its own. However, the growth is disorganized, and is considered a cyst-like growth – called a dermoid cyst. In it, one can find teeth, cartilage, hair, and fat.

Perhaps it is better that these parthenogenetic growths remain as that. Imagine the horror if these growths actually develop into something much worse?

PARTHENOGENETIC ANIMALS

Here are some animals known to reproduce without needing sexual reproduction techniques.

SHARKS

There have been quite a few cases of female Sharks

reproducing without males when in captivity. While some

animals are capable of storing sperm for extended periods of time,

DNA testing confirmed that their offspring had identical genes.

KOMODO DRAGONS

Like Sharks, a captive specimen was able to lay eggs that had her exact genes – and she had never even been in contact with a male of her species.

Given the pattern of Sharks and Komodo Dragons, it’s possible that they are adapting to a life without mates by becoming parthenogenetic for at least some of the time.

TURKEYS AND CHICKENS

As mentioned, Turkeys and Chickens sometimes are able to produce eggs that have not been fertilized but hatch into chicks, anyway. Recent studies show that it’s possible that only one percent of these unfertilized, parthenogenetic chicks hatch.

In what may be a bad idea, some people have created Turkey strains where the survival rate of parthenogenetic chicks are higher.

SNAKES

A 20-foot Python named Thelma gave birth to a clutch of 61 eggs, six of which hatched into healthy female Snakes. Genetic tests revealed all of them to be of the same genes as Thelma, according to a 2021 article written by Katherine Gallagher for Treehugger.

BUT WHAT DOES THIS MEAN?

Discoveries of parthenogenetic species in the animal kingdom (including the potential for it among humans) raises many questions about how organisms use asexual reproduction, to say nothing of other phenomenon like other animal species that can change their sex organs to the opposite, or even animals that have both.

What we should also think about are the circumstances of when we discover them having parthenogenetic actions. When animals are captive and without proper mates, the parthenogenetic abilities activate. Is this the biological backup just in case sexual reproduction is not possible?

Is it also proof that even though parthenogenesis can weaken the overall development of the species, that it is sometimes required simply

to create enough numbers to start off sexual reproduction again?

If so, then the rise of “discovering” parthenogenesis in animals may be a warning sign to us humans that it may be necessary to become even more attentive to how we are affecting the environment around us.

What may be amusing to observe and be a subject of scientific curiosity may already be a warning sign that all living things on earth – even humans – may be in danger if Mother Nature is already activating “backup” population-raising mechanisms in species all over the animal kingdom.

UNTANGLING A REPRODUCTIVE MESS

Aside from parthenogenesis, there are other reproductive mechanisms that aren’t actually, well, what we think of as “traditional reproduction.”

BUDDING

If we take plants and invertebrates (non-backboned) living organisms into account, then some of them create offspring by growing buds that eventually detach from the mother organism – in other words, clones. Female organisms that use this method are also able to reproduce sexually, according to an article by Simon Foden for Pets on MOM.

STORAGE

This is actually a specialized form of sexual reproduction, where the female can actually store sperm from the male for a long time, so it’s possible to fertilize eggs at a much later date, making it look like the animal is having a virgin birth. Some reptiles are known to do this, as written by Kendra Dahlstrom for Pets on MOM.