ANIMALS AND THEIR “SUPER SENSES”

The fact that animals have senses that have a different range from our own should come as no surprise. Indeed, calling them super senses only makes sense from the viewpoint of them requiring radically different ways of perceiving their environments.

But that doesn’t mean that people haven’t been curious about it. Albert Einstein, in response to a letter from an engineer named Glyn Davis, mentioned his fascination for the behavior of bees, migratory birds, and carrier pigeons. And this was in 1949!

5 SUPER SENSES THAT ANIMALS HAVE

Are these so-called super senses just an expansion or new ones entirely?

Now that animal super senses are an accepted idea, the big thing is that we are discovering how animals have an extended or different range of sensitivity for one particular sense, or senses that are either quite different from ours, or radically “redesigned” senses.

- EINSTEINTO SEE IS TO BELIEVE

Let’s start with vision; it is our primary way of knowing the world around us. But other animals may “see” things differently.

THE MANTIS SHRIMP

The mantis shrimp is a visual wonder: Where people have three kinds of photoreceptors, they have – not kidding – about 16. Because of this, they can see infrared, polarized light, ultraviolet waves, and heat, aside from the usual visual range of humans.

Strangely enough, it seems that humans are still better at figuring out one color from another, according to a 2021 article by Ishan Daftardar for Science ABC.

THE OCTOPUS

The Octopus has a special polarized form of vision, and this helps them have better vision in reduced light in the water. It also allows them to see patterns on surfaces that normally wouldn’t show up in regular light.

This makes them better predators as light is filtered out slowly in deeper areas of water, and it allows them to see and send messages to fellow octopi without many other animals seeing it on their skin, according to a 2021 article from Bioexplorer.net.

2. SNIFF AND TASTE

The senses of smell and taste are closely intertwined, and humans are more familiar with their being boosted to high levels when it comes to some animals.

DOGS

Our best friends are definitely the ones we practically accept as having super senses. From tracking sheep and illegal drugs to sniffing out cancer and recently, COVID-19, dogs’ noses have certainly accomplished many feats.

STAR-NOSED MOLE

The star-nosed mole has the unusual ability of being able to smell underwater. The tip of its nose is able to hold an air bubble under water. Through the osmosis of chemicals through the bubble’s walls, once the mole “inhales” a bit of the air in the bubble, they can smell their surroundings underwater.

CATFISH

The catfish, on the other hand, has tongues in all the weird places – and by that, we mean that the catfish has taste receptors all over their body. This allows them to zero in on their targets even if the water is dirty with zero visibility.

MOSQUITOES AND TICKS

In a different twist, mosquitoes can technically “smell” carbon dioxide. That’s how they are able to track the animals (and humans) whom they suck blood from. And as if that weren’t enough, their olfactory parts can detect our sweat, according to a 2019 article written by Nell Greenfieldboyce for NPR.org.

Ticks are very much the same, using organs located in their front legs called Haller’s organs, as explained by Debbie Hadley in a 2019 article for ThoughtCo.

3. PUTTING THEIR EARS TO THE GROUND

Hearing allows us to appreciate our environment in ways vision cannot. But with animal super senses, it can be the primary sense.

BATS

Bats are among the animals whose super senses are most obvious: They use their sensitive hearing to navigate while flying, much in the same way submarines and boats find out about what is below or in the sea. This can be done by emitting ultrasonic waves, which will then bounce off objects and reflect back to the bats. This info can then be translated as a mental map for the bat to use in moving around, according to a 2018 article written by Josie Clarkson for Science Focus.

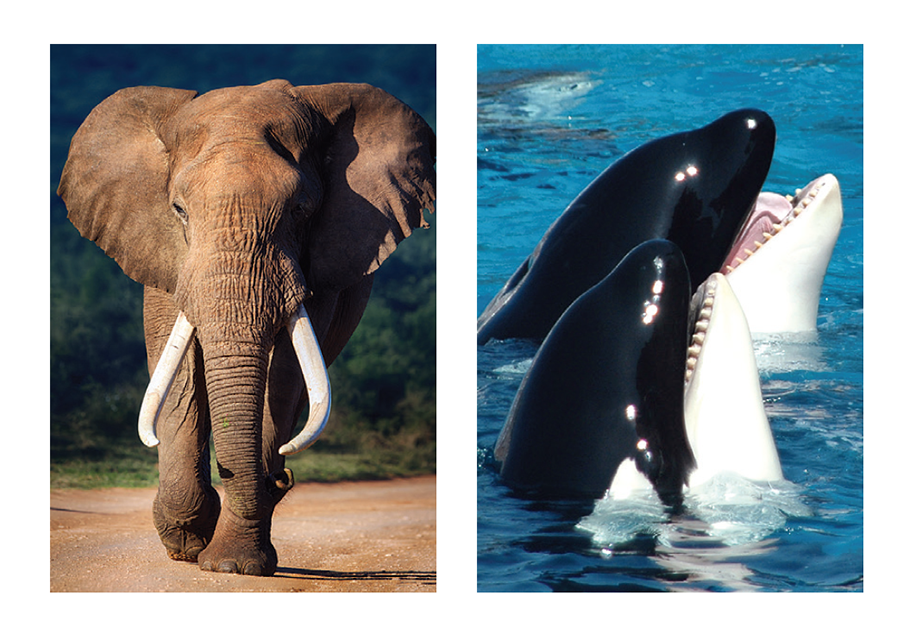

ELEPHANTS AND WHALES

On the other end of the spectrum, elephants and whales use low frequency sound to send messages over long distances – this means that their ears can hear those, too.

Elephants use this low-frequency communication system to coordinate their group movements. Some whales use their ability to hear low-frequency waves for the same reason, but there seems to be more to the whales’ “language” when used in conjunction with infrasonic capabilities.

4. CATCHING A SPARK?

Now, one sense that is definitely not human the ability to detect electromagnetic or electrical fields – and this is a sense that humans don’t have.

SHARKS

Many sharks are able to track fish down by detecting the changes in electrical fields around them as their prey moves through their “hunting zone.”

Supposedly, they can detect a fraction of a billionth of a volt. That means that if you even twitch wrong, they’ll be able to sense that something’s wrong – or right, if they think you’re good food and they’re hungry.

PIGEONS AND ROUNDWORMS

Certain kinds of pigeons and roundworms can sense the earth’s magnetic field, and this allows them to find their direction accordingly.

5. A TOUCHING BIOLOGICAL USE

Now, you may think that the sense of touch may have very few takers for the term “super sense,” but you’d be surprised: Many fish and seagoing animals tend to have an overly sensitive sense of touch, given that the environment they live in, water, carries vibrations very well.

MANATEES

Manatees, for example, have thousands of whisker-like hairs all over their skin, and this helps them figure out data like changes in temperature, currents, and even tidal forces.

It should be noted that the star-nosed mole also has a heightened sense of touch on their noses.

FUTURE SUPER SENSES FOR HUMANS

5And there you have it: These are just some examples of how our friends – furry, scaly, and otherwise – have developed super senses to deal with specific needs and adapt to their environment. It’s no surprise if evolution will further develop not only their senses, but also ours. Who knows? Maybe our descendants will have a version of the ability to sense electrical and electromagnetic fields. Until then, we should be happy that our senses and how we use them work quite well for our purposes.