THE PRAYING MANTIS

By GERRY LOS BANOS

As a child, I spent countless hours watching nature’s dramas unfold among the flowering shrubs and trees in our village’s gardens.

Those were the days before YouTube allowed people to stream countless videos of animals in their natural habitat. Our household didn’t even have cable, and we thus had no nature channel on which I could witness the everyday encounters that occur between animals dwelling in the foliage and underbrush.

So I, fascinated by animal behavior and activities, had no choice but to actually go outdoors and seek out creeping, crawling, hopping, and flying creatures in their natural environment.

In those hours, I witnessed Orb Weaver Spiders shrouding their prey in silk after the unfortunate insects had gotten tangled in their webs. I watched shiny black Carpenter Ants efficiently carrying off Beetle carcasses several times their size up tree trunks to their unseen nests. I waited patiently for Butterflies to land on particular flowers and end up a meal for camouflaged Crab Spiders.

But nothing could compare to the sight of a Praying Mantis stalking and dispatching its prey.

OTHER-WORLDLY HUNTER

There is something almost other-worldly about a Praying Mantis on the hunt. Perched on a branch or twig, the insect patiently surveys the world with oversized eyes positioned on either side of their triangular head, spiked forelegs raised in the characteristic “prayer” pose from which the insect gets its name. Their long, swiveling neck allows the animal to scan the surroundings while keeping their body perfectly still.

When prey is sighted, often a Moth or Cricket unaware that a well-camouflaged predator is nearby, the Mantis patiently waits for the just the right moment. They have excellent vision that allows them to judge the exact distance between themself and the would-be meal.

When the prey comes within striking range, the Mantis lashes out faster than the eye can follow, with their forelegs (called raptorial legs) impaling the victim. The motion is so quick that it barely registers to the human eye: One second, the Mantis is perfectly still; the next, they have a wriggling invertebrate in their grasp and is methodically gnawing away at it with their sharp mandibles.

Mantises are remarkably thorough eaters, consuming almost every portion of their prey. When they are done with their meal, there is often no sign left of the victim, other than a bulge in the Mantis’s thorax.

CHILDHOOD FASCINATION

The first time I actually caught a Mantis in the act of capturing and dispatching prey was by accident. I was probably around twelve and, fancying myself a bug collector, occupied my weekends stalking Butterflies and other insects with a home-made net.

One day, I staked out a spot beside a Jasmine bush that was frequented by colorful Butterflies. To pass the time, I observed Honeybees going about their business harvesting pollen from the Jasmine blooms. I watched one particularly fat Bee buzz around a flower, but the winged creature was seized in mid-flight by something before the poor insect could land.

Moving closer, I saw that the Bee was in the clutches of a light green Praying Mantis a little smaller than my pinkie finger. The predator had been so well-camouflaged that I had mistaken them for part of the plant.

Without hesitation, the Mantis began devouring the helpless Bee, oblivious to the dangerous stinger. In a few minutes, there was only the Mantis perched on the flower, meticulously cleaning the spines on their forelegs.

And so began my childhood fascination with this predatory Insect.

TOP-TIER PREDATORS

I soon developed an eye for spotting Praying Mantises lurking

on branches, leaves, and flowers. The larger ones (either Hierodula manillensis or Hierodula parviceps) were easier to spot, and most impressive when in action.

A couple of times, I was able to witness Mantises half the length of my hand take down Grasshoppers almost their size. On the other end of the spectrum, I once spotted outside our house’s windowsill a tiny Mantis nymph, less than an inch in length and probably just a few days old, methodically consuming a Mosquito that they had likely captured in mid-flight.

FORMIDABLE INSECTS

Later, I would read accounts in books and magazines of large Mantises in

the United States attacking and killing Hummingbirds. Most experts believe that the culprits are Chinese Mantises (Hierodula chinensis) who can grow over four inches long, much larger than the native American varieties. These were brought into the country during the 1800s to control insects who destroy crops.

Unfortunately for farmers and gardeners, Mantises do not distinguish between beneficial and harmful insects. While they will consume crop-damaging Locusts and Weevils with gusto, they will likewise make a meal of important pollinators such as Butterflies and Moths. And it turns out they will consume non-insect prey as well.

Nowadays, one can find several videos on the internet of encounters between Praying Mantises and various other creatures, such as small Snakes. Lizards, Frogs, or even Mice, and more often than not, the Mantis comes out the winner. (I suspect that a number of such “encounters” are staged as though there are documented instances of Mantises eating non-insect prey in the wild; reptiles, amphibians, and mammals do not make up a regular part of their diet.)

Though generally thought of as apex predators, Mantises are themselves often eaten by larger lizards and birds, as well as by insectivore mammals,

such as Bats and Tarsiers. In the insect world, however, the only fellow insects Praying Mantises need fear are others of their kind.

MATE EATERS

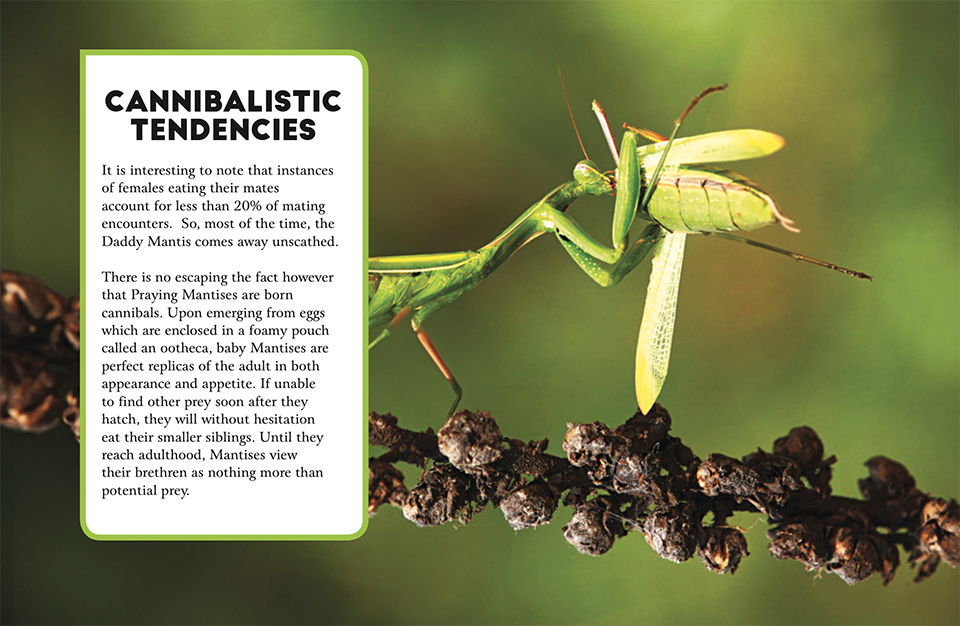

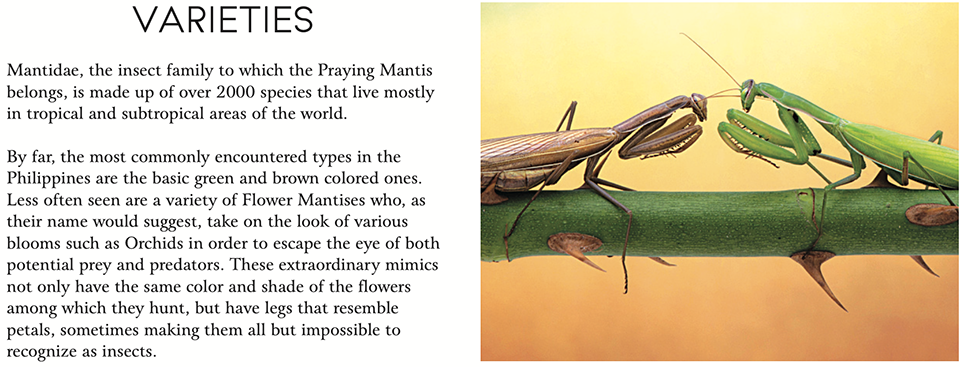

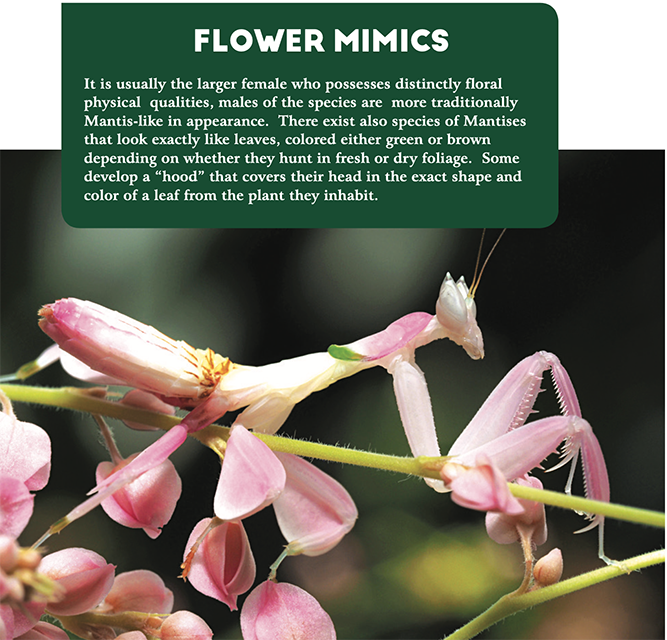

Among the most popular images people have of the Praying Mantis is that of them as a mate-eater. Conventional wisdom has it that the female Mantis, who is generally larger than the male, often devours her mate.

Many, I’m certain, have seen photographs or watched videos wherein the female Mantis, during the act of mating, twists her flexible thorax to face the male behind her, grasps his head with a foreleg, and proceeds to

eat him, in effect decapitating her partner.

The now-headless male Mantis, seemingly unperturbed, continues to carry out his reproductive duties and, unless the female decides to eat the rest of him, can remain mobile for hours or even days after. This is due to the fact that several parts of a Mantis’s nervous system, like that of many insects, are not controlled by their brain but by other organs distributed throughout the rest of their body.

The most common theory behind the phenomenon of female Mantises eating their mates is also the most basic: the female is hungry, and the male presents a convenient, unresisting food source. Some etymologists believe that the action is also a form of self-defense, since once the male has satisfied his instinct to procreate, he may then give in to the urge to hunt and feed with the female being the prey.

Other theories suggest that such cannibalistic behavior helps ensure stronger, healthier offspring, since a well-fed mother-to-be is better able to nourish developing eggs in her body.

There may also be genetic advantages achieved by the male’s sacrifice. A fairly recent study showed that upon being consumed, a male Mantis is able to pass on more of his genetic material to his resulting offspring compared to one who is not eaten by the female Mantis bearing his eggs.

TERRITORIAL

Regardless of appearance, each and every Mantis is a predator and, unless it’s mating season, is driven by the singular instinct to capture and consume other living creatures in order to survive.

It is for this reason that all Mantises are fiercely territorial; most predators require a substantial area in which they, and only they, can hunt. Mantises will defend their chosen territory fearlessly, assuming a threatening pose with forelegs outstretched and wings fanning out to make themselves look larger.

If the intruder is not intimidated, the Mantis may strike out with their raptorial legs, even if the foe is several times larger.

POPULAR COMPANIONS

Of all insects, Praying Mantises are among the ones

most often kept as animal companions since they require very little maintenance. They are especially popular in classroom terrariums which allow children to observe their habits and behavior.

In my younger years, I would occasionally capture a large Mantis and place them in a dry aquarium with branches and leaves (I learned early on that it was not a good idea to keep more than one Mantis in a single container).

Over the course of a week, the Mantis would grow fat on a diet of live Cockroaches, never in short supply in our house. I would drop the Roach into the enclosure and the insect would scamper around looking for a way to get out. Eventually, the Cockroach would come within a foreleg’s reach of the aquarium’s main resident, who would quickly snatch them up and devour them, not bothered at all by the fact that Mantises and Cockroaches are closely related in the insect family tree (both belong to the same superorder Dictyoptera).

As mentioned earlier, Praying Mantises are relatively easy to care for. It didn’t take much effort to sustain the Mantis I kept. I simply had to keep the enclosure clean (which wasn’t difficult since they hardly left any leftovers), occasionally replace the branches, and once or twice a day, toss in a live insect for them to stalk and eat.

The Mantis actually didn’t seem to mind being held captive and made no effort to escape. Sometimes the insect would explore the area, clambering around the stalks and leaves, probably checking for any prey they had missed. Most of the time, they would simply sit still on a branch, “praying” until meal time.

It often didn’t take long, less than a week, before I would realize that there was something very unseemly about keeping such a magnificent creature in a cage. I would then take the Mantis to the vacant lot beside our house to set them free.

Usually, I’d lay them upon the branch of one of the many Malunggay trees that grew in the lot since that was where I had found it in the first place. The Mantis would then climb further up the tree and take a position among the leaves, waiting for some unlucky insect to wander within reach.

Camouflaged atop their green throne, they ruled over all they surveyed as the number one predator. Or at least until they were spotted by a larger Mantis or one of the many Brown Shrikes patrolling the area.