It was my wife who first spotted the bird fluttering helplessly over 20 feet above us while we were walking our Dogs around the neighborhood. Even as I moved in closer to get a better look, I already knew what had ensnared the poor creature.

It was the height of summer, and every day, the horizon was dotted by colorful kites of all shapes and sizes. Inevitably, though, many of those would come crashing down, leaving in their wake a trail of strong, nearly invisible string draped over tree branches and wires.

One of those lengths of string had gotten entangled in the wing of the bird, which I recognized as a male Yellow-Vented Bulbul, dangling from a telephone wire.

UNPLANNED RESCUE

It took some effort to trace the path of the offending string to a nearby tree. Using a broom, I managed to snag one end of the line and cut it, allowing me to lower the Bulbul so I could get ahold of the bird. I found that the string was so tightly wound around one wing that I couldn’t untangle it and instead had to carefully cut it away.

After freeing the wing, I had intended to keep the bird for a little while and observe whether it was injured, but he apparently had other plans and surprised me with a strong flapping of wings that made me lose my grip.

Mr. Bulbul fluttered off and disappeared into the foliage.

DEADLY AIRBORNE WEBS

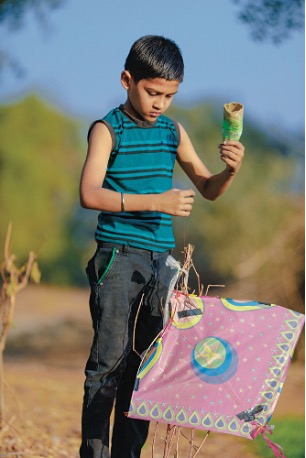

Kite flying has long been a popular hobby all over the world. It is an activity that affords pleasure to countless people of all ages and income levels. What many fail to realize, however, is that the irresponsible use of kites can mean death for the animals who traverse that same space many, many feet above the ground.

In India, many occasions such as Makar Sankranti (a Hindu festival that celebrates the arrival of spring) are marked by kite-flying competitions. The kites used in such contests are tethered to a synthetic string known as manjha, which is coated with powdered glass that allows it to cut the lines of other competing kites, according to an article by the Wildlife Trust of India for Global Living.

In certain places, however, kites are flown in such volume that they become hazards to many bird species who fail to see the obstacles in their flight paths. Parakeets, Owls, Crows, Pigeons, Sparrows, Falcons, Eagles, Lapwings, Peafowl, Vultures, Geese, and Cranes have fallen victim to kite string injuries, suffering cuts and fractures after colliding with the glass-coated string.

Many cities in India have banned the sale and use of manjha

and similar kite string upon the urging of nature conservation organizations, but the “death thread,” as some environmental advocates have dubbed it, still manages to find its way into the hands of kite enthusiasts and continues to wreak havoc on the flying population.

In 2018, the forest department officials reported that 4,000 birds were rescued in the city of Gujarat by the state forest department after the mass kite-flying during the Makar Sankranti festival.

A POTENTIAL DEATH TRAP

While kite-flying festivals may not be as ubiquitous in other parts of the world, pretty much every country has a good number of kite enthusiasts. And it’s easy to understand why so many people love the activity. Be it a homemade construct crafted from crepe paper and bamboo or a state-of-the-art contraption that utilizes space-age material, every kite is a joy to behold as it dances in the air, painting a pattern of colors against the canvas of blue sky.

None of them, however, is immune to the pull of earth’s gravity or the whims of the wind. And quite often, even the most skillfully built kite will come spiraling down to the ground.

Sometimes, the owner heads out in search of the downed kite, but often in the case of homemade or cheap models, the kite is simply given up for lost. Thus, its string remains stretched between tree branches or utility wires, nearly invisible to the eye, and is potentially deadly to anyone who gets entangled.

Type in “kite,” “string,” and “birds” into the Google image search engine and you’ll be greeted by dozens of photographs of avians who were injured or killed by kite string. Some of the most disturbing ones show the skeletal remains of birds hanging from a line, their carcasses still sparsely feathered.

The most dangerous types of common kite string are those made of synthetic, non- biodegradable material. Such lines can remain in place for years, a constant threat to flying creatures. But even biodegradable strings, such as those made from cotton, can be dangerous. The string that had snagged the wing of the Yellow-Vented Bulbul I rescued was common, everyday sewing thread.

EDUCATION AND DISCIPLINE NEEDED

In India, several conservation organizations run educational campaigns, especially when festivals that feature kite flying competitions are about to be held. Such programs aim to teach the young in particular that using manjha and similar synthetic material can be a danger to wildlife.

Such campaigns also encourage the retrieval of fallen kite string so that they no longer pose a threat.

Similar educational programs are needed all over the world, including the Philippines which has more than its share of kite enthusiasts. Aside from being schooled with regard to responsible kite flying, Filipinos should also be made aware about the importance of cleaning up the aftermath of kite crashes.

It’s not uncommon to come upon seemingly endless strands of twine or thread draped over trees or man-made structures in both city and province. People should be taught that it’s worth a few minutes of their time to cut up or disentangle these to ensure the safety of wildlife.

A PREVENTABLE STRING OF DEATHS

Shortly after rescuing the entangled Bulbul, I came upon another incident involving a bird and an unlucky encounter with kite string, this time in the UP Diliman Campus where I teach.

A Night Heron was found dead after their wing had gotten snagged by abandoned kite string. The carcass was hanging literally hanging by a thread from a tree branch. One can only imagine the pain and fear the poor bird went through before succumbing. One can also wonder how many more similar tragedies are never discovered.

A little care and effort on our part could ensure that fewer animals suffer the consequences of this human hobby.