It has been half a year since the COVID-19 pandemic wreaked havoc in the country and the rest of the world; yet, to date, scientists are still scrambling to find a cure. Because of the virus killing hundreds of thousands of people as well as bringing economies to their knees worldwide, many are hoping that a vaccine will bring a stop to the spread of the disease.

As promising as it may sound, a vaccine is not an end-all. be-all panacea for our COVID-19 problems. It is indeed crucial that a cure be developed soon, but it is as equally important that we put our efforts into preventing the transmission of diseases that are shared by animals and people, also referred to as zoonotic diseases.

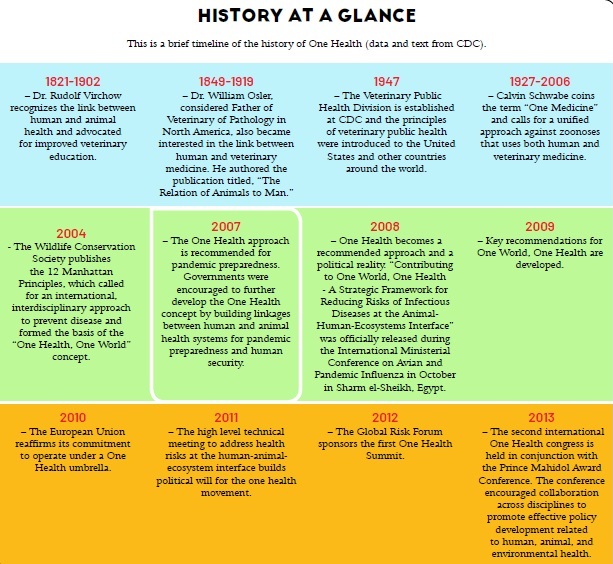

This is where the One Health concept comes in.

What is One Health?

One Health is an emerging concept that aims to bring together human, animal, and environmental health. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) defines One Health as “a collaborative, multisectoral, and transdisciplinary approach – working at the local, regional, national, and global levels – with the goal of achieving optimal health outcomes recognizing the interconnection between people, animals, plants, and their shared environment.”

It’s all connected

One Health stemmed from the “One Medicine” concept by Dr. Calvin Schwebbe, wherein he stressed the importance of the similarities between human and veterinary medicine, and “the need for collaboration to effectively cure, prevent, and control illnesses that affect both humans and animals.”

Humans vs Vet Medicine

Achieving harmonized approaches for disease detection and prevention is difficult because traditional boundaries of medical and veterinary practice must be crossed. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, this was not the case: researchers like Louis Pasteur and Robert Koch, and physicians like William Osler and Rudolph Virchow, crossed the boundaries between animal and human health.

This is a species-spanning medical practice and collaboration, not only in the area of zoonoses or inter-species infection by pathogens, but also when it comes to diseases and issues usually categorized as non-zoonotic, such as tetralogy of Fallot (a congenital heart disease), infiltrative heart diseases, heart murmurs in macaws, congestive heart failure in dogs, dilated cardiomyopathy in dogs, neoplasms, acquired metabolic disorders necessitating medical procedures by physicians and veterinary colleagues, non-infectious diseases, carcinomas, sexually transmitted diseases, as well as transmissible sarcomas. This is a mutually beneficial paradigm in that one field may benefit from the advancement of the other.

Human and animal health has been threatened by antimicrobial resistance, environmental pollution, and the development of multifactorial and chronic diseases. Some, such as the recent SARS-CoV-2, are believed to be an example of new diseases. As Rudolph Virchow, Father of Modern Pathology, said unequivocally, “Between animal and human medicine, there is no dividing line, nor should there be. The object is different, but the experiences obtained constitutes the basis of all medicine.”

I have talked to all kinds of tertiary-level experts in human medicine – cardiologists, oncologists, interventional radiologists, neurologists, gastroenterologists, pulmonologists, OB-GYNs, rehabilitation medical doctors, even diagnosticians, ophthalmologists, and molecular epidemiologists – many of whom are my friends, while others are either acquaintances or strangers, and almost always, I get the same surprised reaction from them at the resemblance of terminologies and veterinarians use.

A physician friend was surprise when I said we also used Arthur Guyton and John E. Hall’s physiology textbook. The science of bodily function is quite similar in both field.

Common sense… of smell

Let’s be honest: Not all diseases need to be treated with drugs or surgery. I once had the privilege of being treated by a physician who was a rehabilitation medicine consultant. He had a chihuahua who, for the longest time, was considered their “baby” and was the center of their attention until he and his ophthalmologist wife welcomed a new addition to their family: their own baby. They had to focus their full attention on their newborn and unfortunately needed to change their living arrangements, including where the dog would sleep. All these sudden changes in the house gave the dog separation anxiety.

The dog reacted to this change by barking nonstop all night long. This created a stressful situation for the whole family, with the animal feeling left alone and the humans distraught by the noise. My friend asked me if there was any medication to sedate or stop the dog from barking excessively.

I instinctively thought of a solution without the use of sedatives or barbiturates. I asked my friend to find unwashed clothes of his and put those in the dog’s cage during the night. I was attempting to calm the dog by giving him something familiar – in this case, my physician friend’s “presence” – as the canine might find it comforting, quite literally like a security blanket.

After some time, I asked my friend if it worked, and he said that the chihuahua had been soundly sleeping since then. Wow. That’s the elementary principle of pheromones, a not-well-understood concept, which can be applied as an alternative approach to health.

Zoonotic diseases

There many instances showing how the health of people is related to the health of animals and the environment. As mentioned earlier, some diseases can be shared between animals and humans, and are known as zoonotic diseases. Here are a few examples.

1. Rabies

Rabies is very much feared but widely misunderstood in the Philippine setting. It is a very common viral disease communicable to man through animal bites and scratches. Here in the Philippines, it is declared as widespread and has caused numerous deaths, such that it had to be declared as endemic.

A law was enacted to prevent, control, and eradicate rabies, known as the Anti-Rabies Act of 2007, which also includes animal welfare responsibilities towards companion animals.

Animals suspected to be rabid must be captured, isolated, and observed. For this to be mandatory, all LGUs should provide the veterinary office with quarantine facilities.

2. Ebola

The Ebola virus causes a rare but serious viral infection. It is highly fatal if left untreated. The virus causes two simultaneous outbreaks in 1976: one in South Sudan and in a village near the Ebola River after which the disease was named.

According to the WHO, fruit bats are thought to be natural Ebola virus hosts. Transmission occurs when humans come into “close contact with the blood, secretions, organs, or other bodily fluids of infected animals like fruit bats, chimpanzees, gorillas, monkeys, forest antelope or porcupines found ill or dead in the rainforest.”

The virus spreads human to human through direct contact with the blood or bodily fluids of (and even objects belonging to) a person who is infected or has died from Ebola.

3. Influenza A virus subtype H1N1

The virus was first detected in the United States in 2009. It soon spread quickly around the world. It “contained a unique combination of influenza genes not previously identified in animals or people,” according to the CDC.

The CDC further stated that since the introduction of the virus in 2009, “H1N1pdm09 has circulated seasonally in the US causing illnesses, hospitalization, and deaths.”

The organization estimates that since the detection of the virus in 2009 until 2018, there has been at least 100.5 million illnesses, 936,000 hospitalization, and 75,000 deaths.

The organization estimated that since the detection of the virus in 2009 until 2018, there has been at least 100.5 million illnesses, 936,000 hospitalizations, and 75,000 deaths.

Researchers from Mount Sinai Hospital in New York said that it originated from pigs in a small region in mexico and has been present for 10 years until a mutation gave it the ability to infect humans.

4. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2)

The newly-discovered SARS-CoV-2 causes a disease (COVID-19) that is highly contagious and is currently spreading throughout the globe. As of this writing, it has affected over 14 million people, with 600,520 deaths and counting. Although it is easily transmitted from person to person, the fatality rate remains low at 3%.

Mild to moderate symptoms will appear for most people infected with the disease and they are suspected to recover without special treatment. However, older people and those with underlying medical conditions like heart or lung disease, diabetes, and cancer are more susceptible to severe symptoms.

According to an article published in Nature Medicine, scientists found that the COVID-19 virus is similar to viruses found in bats and pangolins.

Striving for progress

The future of One Health is at a crossroads, with the need to more clearly define its boundaries and demonstrate its benefits. Interestingly, the greatest acceptance of One Health is seen in the developing world where it has had significant impact on infectious disease control.

The willingness to learn from each other is the single most important determining factor. We all need to learn, relearn, and unlearn; otherwise, we would all be repeating the same things and we would all go back to square one, even with all the furious paddling to reach the objective using the same paradigms.

This appeared in Animal Scene magazine’s September-October 2020 issue

You might want to read:

– Coronavirus sniffing dogs introduced at Helsinki airport to identify infected passengers

– Most people say coronavirus pandemic silver lining is more time with animal companions

– Coronavirus helps reduce death toll of Sri Lanka’s threatened elephants