August 12, 2014 was a very sad day. A male Philippine eagle was confirmed dead at Mount Apo. We had trapped and tagged this bird with radio and GPS trackers. But four months later, our team found his decaying body at a forest slope. A gunshot killed this eagle.

This left a seven-month-old eagle chick fatherless. At this tender age, the eaglet relied entirely on the parents for food. But with this male eagle gone, the female eagle might not be able to provide enough food. The eaglet can die.

Mother’s love

Miraculously, the mother’s eagle copes. Philippine Eagle Foundation (PEF) biologists and forest guards from the Sinabadan Kag Tugallan – a Bagobo Tagabawa organization – monitored the female eagle and her young. Both also had their own radio and GPS trackers. Our indigenous counterparts named the juvenile “Sinabadan” and swore to keep the bird, now their namesake, away from harm. While the female eagle doubled up on her food deliveries, Bagobo Tagawa forest guards trailed the young eagle and kept the bird safe.

Grit and hard work paid off. Hardwired to be free-living and independent, Sinabadan began her slow journey out of her parent’s territory exactly two years after he father died. She was almost three years old then; already an able hunter and fully self-sufficient.

Sinabadan is the world’s first juvenile Philippine eagle reared successfully to independence by a single eagle parent in the wild.

Thriving

Sinabadan is now six years old and may start breeding soon. But first, she has to find a mate and a forest territory that she and her partner can call their own.

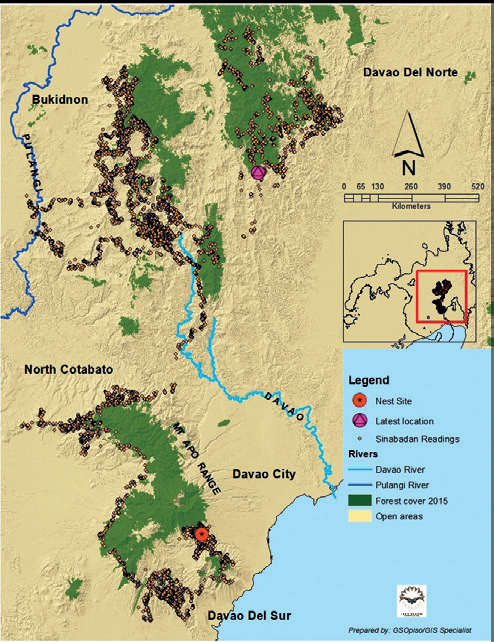

A total of 47,459 GPS locations were collected over six years of remote monitoring via a total of four GPS transmitters strapped on Sinabadan’s back. This meant we had to trap Sinabadan three more times to replace units that expired. As of this writing, she was over 80 kilometers away from her hatch site and the village of her former Bagobo Tagabawa guardians. She would nest soon, and we hope that it’s in a safe forest where her closest human neighbor would welcome and treat her as special.

Cautious relocation

Away from the watchful eyes of her Bagobo Tagabawa guardians, Sinabadan took a perilous voyage. But because she had trackers, the PEF teams could intervene if needed. For instance, during her near circumnavigation of the 90,000-hectare Mount Apo range from 2016 to 2017, the team checked on her whenever she was very close to villages. The team watched to assess her health. They also convinced villagers close by not to shoot or harm the bird.

Sinabadan left Mount Apo for good in November 2017. Getting to the next big forest meant flying over peopled landscapes. Rainforests once carpeted 90% of ancient Mindanao but forest cover has now been reduced to a mere 20% of the original. Mindanao’s forests now are mostly fragments in a sea of farmlands, orchards, and open areas.

Remarkably, Sinabadan used small patches of forests as her cover and pitstops. From a naive juvenile, she had grown wary through time. She dispersed secretly and gradually, covering distances of no more than 2 km daily. She also followed riverine forests, such as those along Davao and Pulangi Rivers. At Pulangi, PEF biologists saw her chase monkeys. Flying lemurs, palm civets, hornbills, and other food animals were also recorded at forests were Sinabadan temporarily took shelter. These data on how a juvenile eagle used and flied acorss a bigger, human-dominated terrain were all new to science.

This appeared in Animal Scene magazine’s May-June 2020 issue.

Jayson Ibanez is the director of the Philippine Eagle Foundation.

You might want to read:

– PH eagle family found in Zamboanga city

– Critically endangered Philippine eagle rescued in Zamboanga del Norte

– The Philippine eagle grips into existence as threats continue to kill them