One of my favorite exhibits at the National Museum of Natural History in Manila comprised of several Dinosaur skeleton replicas, including an almost 10-foot-tall hind leg of a long-necked Sauropod known to science as Camarasaurus grandis.

My brother and I have always loved Dinosaurs, ever since we got hooked by a bizarrely fun 1990s cartoon series called Dino-Riders, which combines two things many boys love most: lasers and Dinosaurs (the heroes also sported 1980s mullet hairdos so that’s a plus).

My favorite was – and still is – Triceratops, but I’ve always found the giant long-necks to be among the most interesting. Diplodocus, Brontosaurus and Brachiosaurus are the three most iconic, but who among them was actually the longest?

BIG DISCOVERIES

With approximately 300 discovered species, Sauropods (ancient Greek for “lizard foot”) include the largest animals ever to have walked the Earth. They were herbivorous and spent most of their time grazing on grasses, ferns, and trees. Though some like the Ohmdenosaurus were small at about 12 feet long (just about as long as a car), there were many that exceeded 100 feet in length. Imagine animals much longer than a full-sized NBA basketball court.

As a greater number of paleontologists (fossil scientists) learn new information about Sauropods, we’re getting to know more about these giants each year. When my brother and I were still watching Dino-Riders, the longest confirmed Dinosaur was Diplodocus, who grew just a little over 100 feet.

Modern paleontologists have since unearthed evidence of much larger Sauropods, though often from fragmentary bones instead of complete skeletons. There’s the 120-foot-long Seismosaurus, now thought to be just an unusually large Diplodocus (think Yao Ming for humans), Argentinosaurus, Ultrasaurus, Sauroposeidon, and others who top out at a little over 100 feet.

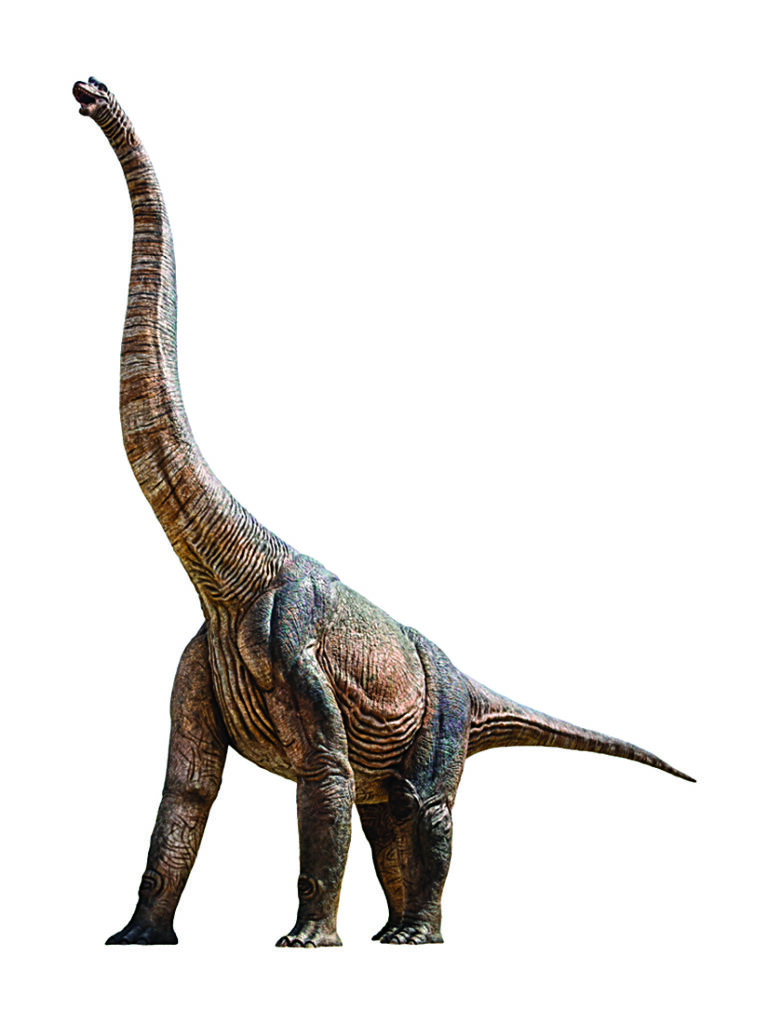

Long-necks. Sauropods had distinctive long necks to allow them to graze on all manner of vegetation, ranging from grasses to trees. Supersaurus, the longest accurately-verified sauropod at 130 feet, would have looked a lot like this. (Daniel Eskridge)

HISTORICAL CHALLENGE

Perhaps the largest of all time was Amphicoelias, a long-neck who supposedly grew twice as long as Diplodocus – except the only evidence of their existence was a single piece of badly-damaged vertebra measuring pretty much five feet tall (nearly half the height of the leg of the Camarasaurus on display at the National Museum in Manila). When reconstructed, the vertebra would have actually been nearly nine feet tall.

The problem? The vertebra itself has been missing since 1877, so there’s zero science-based proof the animal actually existed.

“It is highly unlikely for an entire adult Sauropod skeleton to overcome the vagaries of the fossil record,” explains paleontologist Kristi Curry-Rogers. “It’s not at all surprising that complete specimens are hard to come by.”

Thus, most Sauropods are found as incomplete fossils. Seismosaurus was known only from part of their tail, some ribs, and a pelvis. Bonitasaura was known only from a jumbled heap which included two leg bones. Titanosaurus was known only from a single tooth.

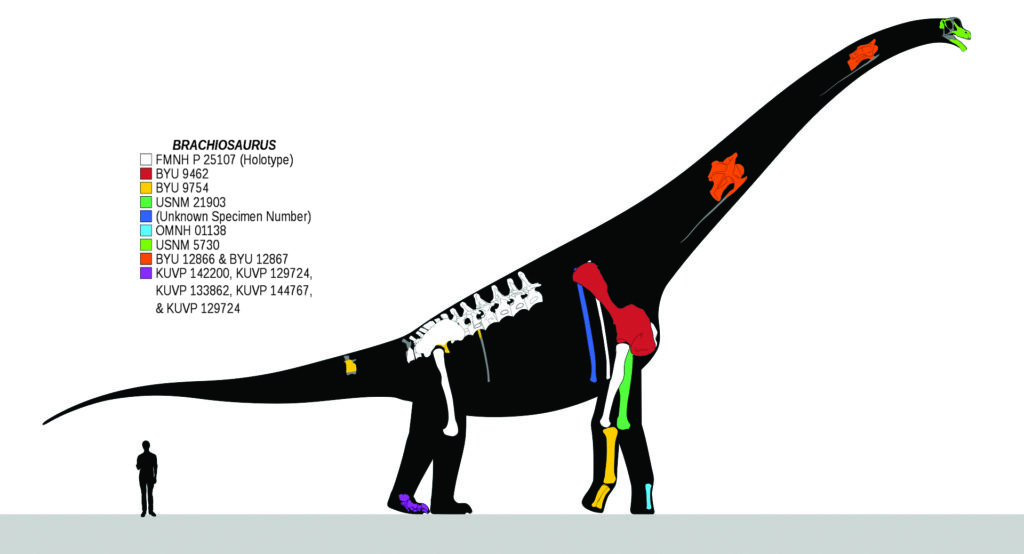

Pieces of a Puzzle. This illustration shows just why it’s so difficult to establish accurate sizes for many Dinosaurs. The fragmentary bones of various individuals and specimens – sometimes taken from different areas – are pieced together to reconstruct what the animals must have looked like in life. Just like humans, Dinosaurs of the same species can also vary in size, adding to the confusion. Still, there’s always hope that a Dinosaur in great condition can be unearthed. (Slate Surprise)

SIZE MATTERS

So who was really the longest? Despite these animals being the size of buildings, they’re pretty hard to come by.

Based on available fossils, the longest reliably-measured Sauropod was a cousin of Diplodocus called Supersaurus, who would have grown around 130 feet long – a titan by any measure!

Until we find more fossils, this super-sized Sauropod is our top winner.

Sauropod Surprise. Animal Scene author Gregg Yan (who is not very tall anyway) attempts to demonstrate the scale of the nearly 10-foot-tall leg bones of a Camarasaurus grandis, a 50-foot-long Sauropod who inhabited the Western United States during the late Jurassic period, around 150 million years ago. (Gregg Yan)

A Giraffatitan, the most recognizable type of Brachiosaur, gazes down on Gregg and Jimbie Yan. (Jan Bautista)