The smart and fast racing pigeons of today are a far cry from their ancestors centuries ago. While homing pigeons are known to have the instinct to “go home” with some having been trained to send messages, they do not do so in fast or clever, stubborn ways that the modern racing pigeons do: soaring through the wind at a speed of 100 to 160 kilometers per hour, flying straight, and going home to their loft within 12 hours, even from 1000 kilometers away.

These racing pigeons are a product of continuous breeding by pigeon fanciers who saw the need to develop these birds into winged athletes capable of flying extreme long distances at a short amount of time.

While early modern racing pigeons were developed through the efforts of legendary pigeon racers Henri Janssen and sons Louis and Jef of Arendonk, Belgium (giving rise to the Janssen-Arendonk pigeons), and Stichelbaut Alois (of the Stichelbaut strain of pigeons), it was ultimately the persevering efforts of the renowned pigeon journalist Piet de Weerd, otherwise known as Pigeon Professor, which made a big headway in the creation of the modern day “overnight long-distance” pigeons.

De Weerd’s partnership with several breeders and pigeon racers was the key in this development. Using knowledge gained from personal experience and tapping into winningest pigeons at the time, the Pigeon Professor chose birds based on body conformation, pigeon vitality, excellent racing records, and a certain stubborn attitude he called “pigeon mordant”. Eventually, De Weerd engineered pigeon bloodlines that became the foundation of modern overnight long distance pigeons: Jan Aarden and Maurice Delbar strains, Josef Vandenbroucke’s Didi Line, and later, Etienne de Vos’ “Kleine Didi”, the last two being the result of several years of selection and inbreeding.

A pool of good genes

Every successful fancier and pigeon racer owes their success to dedicated and continuous assessment of breeding techniques. Many famous fanciers may have started with the winningest pigeon, but sustaining their wins came from how they bred and kept the excellent line running through the blood of their pigeons. (You may win the race this year, but without the knowledge and know-how of preserving your pigeon’s characteristics into the next batch of racers, this win might not be repeated next race season.)

There are generally two types of breeding, depending on the goal: interbreeding and outcrossing.

Interbreeding can be classified further into line breeding and inbreeding. Line breeding is the interbreeding of individual birds coming from the same origin or ancestor. This is done when you want to preserve a desirable characteristic from the ancestor and stabilize the genes of a certain line of pigeons. Usually, it involves pairing pigeons of relations, such as a grandfather to a granddaughter, aunt to nephew, or uncle to niece, but never in a closer proximity as sire to daughter or dam to son. Line breeding is an excellent way to preserve your line without making the genetic make-up of the bird too similar.

In contrast to line breeding, inbreeding is the pairing of individuals to their immediate family member, such as sire to daughter, dam to son, or sister to brother. However, line breeding and inbreeding should be done only to an extent. While inbreeding results to heterosis, meaning potency and robustness to the existing characteristics, repetitive inbreeding will, in Skytime, decrease this vigor and result in producing dumbed-down versions of your line, or what we call “inbreeding depression”.

Inbreeding and line breeding should be used in a perceptive and discerning manner. You should always be on the lookout for undesirable characteristics in the offspring and cull them from your loft. Moreover, I strongly suggest that line-bred and inbred pigeons be used only as breeding stock and not for racing. Use them as breeders to be outcrossed to pigeons with the same genetic pool. In layman’s terms, race only the pigeons which are offspring of two unrelated pigeons, but with same characteristics — pigeons with good records who excel in long-distance races.

Sibling breeding, or the pairing of sister-brother pigeons, is another way to breed. It is usually done to develop the good genes of two birds with identical traits. But do not sib-breed just for the sake of it. Like humans, not all siblings have the same good characteristics. Use this technique only when the sibling birds both perform excellently in races. Two siblings, two super racers, one genetic trait — sib-breeding would secure the good genes and duplicate the winning characteristics, creating potency in the genetic pool.

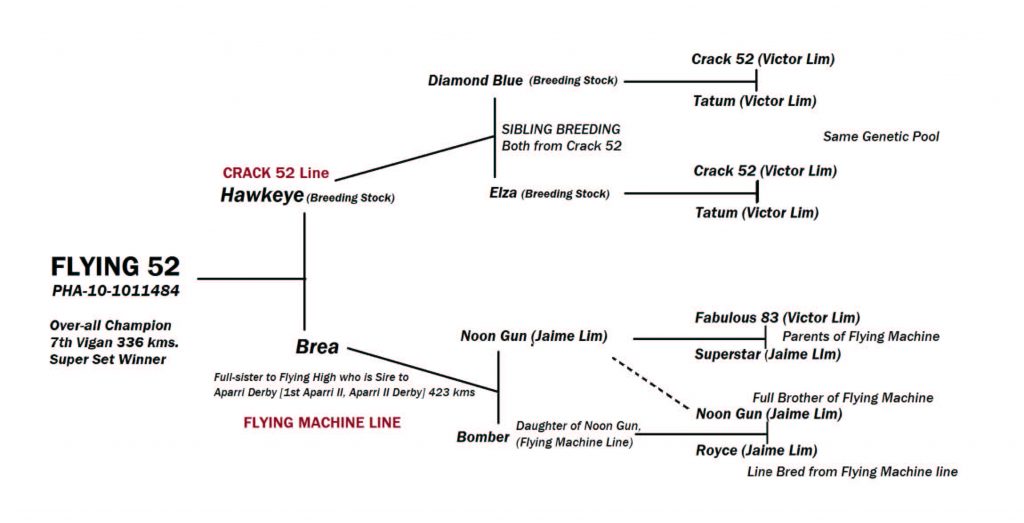

Inbreeding and line breeding can stabilize and, later on, create unique strains. In my case, I have used these techniques to keep my Crack 52, Flying Machine, and Flying 52 strains. Without these methods, these birds’ amazing characteristics would have been forever lost in time. If I hadn’t been able to line-breed my Crack 52 and Flying Machine pigeons, I wouldn’t have been able to outcross the two to create my Flying 52 pigeon, which I later on developed as a line of their own.

Now, while interbreeding can be used to stabilize and keep a pigeon line or to breed stock birds for future breeding, the key to winning races lies in another breeding technique, outcrossing, which will be discussed in the next issue.

This appeared in Animal Scene magazine’s April 2019 issue.